Since research into marginal texts is young and has yet to develop a standard language with which to describe the phenomena we encounter in margins and interlinear spaces, we developed our own language for our observations of practices in the margins of early medieval manuscripts. Here is our list of definitions.

Marginalia: the Latin word marginalia refers collectively to all notes and markings that were entered in the margins of a manuscript, be it sophisticated lengthy comments on the text, diagrams, corrections, random doodles or chapter numbers, running titles and signs that marked interesting points. We decided to use this generic term to encompass the various phenomena that take place in the manuscript margins irrespectively of what form they have and what purpose they served.

We further distinguished several types of marginalia described in the database entries.

Types

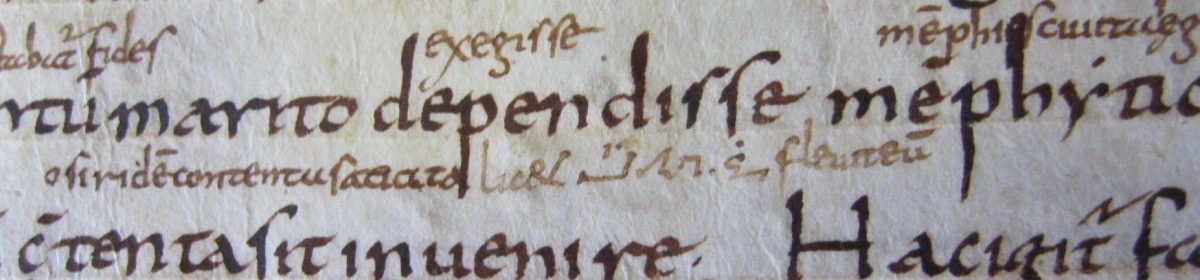

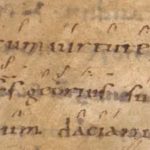

Annotations: capsules of text entered in the margins (marginal annotations) or between the lines (interlinear annotations) of a manuscript that are related to the text in the main window in an obvious manner. Usually, annotations comment on the text or translate individual words, phrases, and sentences. An example of marginal and interlinear annotations are glosses, which clarify or explain difficult words in the text.

Attachment: text entered in the margins or on pages left empty that has no obvious relationship to the text in the main window. Attachments usually appear in a manuscript simply because there was some blank space that could be used for small compositions or to note down something of interest – charters, liturgical chant, excerpts or poems.

Commentary: a continuous text inserted in the margins and in between the lines of a text that comments on this main text. The appearance of commentaries was necessitated by works that required exposition, such as texts of school authors or texts that were studied in certain contexts. A notable example is Servius’ commentary on the works of Virgil, which came into being already in Late Antiquity. Commentaries can have the form of separate texts (so-called running commentaries) or of marginal commentaries, of which this database records only the latter. The difference between a commentary and annotations is not necessary strict and depends on whether the annotations display a certain design or unity (e.g. because they were all entered by the same hand, because they can be shown to reflect a single purpose or theme, or because the manuscript was from the outset intended for the insertion of marginal text).

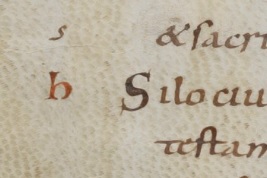

Correction: an alteration of the main text made because the text contains an error or a lacuna. Corrections may be made directly in the text or above the line, but they can also be made in the margin. In that case, an omission sign is usually used to link the correction or the omitted material in the margin with the place in the main text where they belong. If a particular convention of omission signs is used in the manuscript, for example d-shaped and h-shaped sigla, these are recorded in the database as well.

Probation: marginalia entered in the margins or on empty pages by scribes testing the new pen or new ink. They may have the form of words or verses (commonly from the Psalms), but also drawings and ornaments.

Apart from various types of marginalia, we also decided to record the presence of certain specific phenomena relevant for the understanding of specific early medieval annotation practices. They do not constitute separate marginalia types, but are features present in these types (such as when annotations or corrections were made partially in Tironian notes, or neums were used in attachments).

Specific phenomena

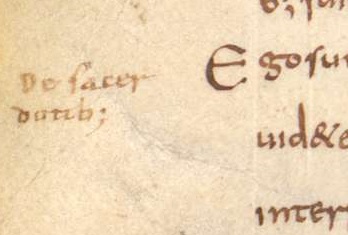

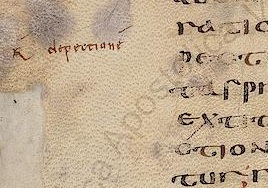

Catchphrase: a word or a phrase that calls attention to the subject treated in the main text, usually repeating word(s) from the main text. Catchphrases usually have one of the characteristic forms: the combination of the preposition de and a subject (e.g. de lupercal, de Tarquinio, de fletu); questions (e.g. quid sit symbolum, cur populus herculi sit consecratus); or a statement that expresses the gist of a given passage (e.g. rudere proprium est asinorum). Sometimes they function as an index for the reader. In some cases, catchphrases are nothing more than interesting terms or word forms copied in the margin.

Construe marks: graphic symbols that clarify Latin sentence structure by adjoining together words that are in grammatical agreement or connecting a deictic pronoun to the word it refers to. They have the shape of a combination of dots that appear above or below the respective words, usually forming pairs (but in some cases more than two words can be linked together).

Correction sign: a sign that points out lines or verses in need of correction. In some cases, emendation was carried out, in other cases only the correction sign is present.

Critical sign: a sign that serves the critical assessment of a text, whether the criticism is textual or literary or whether it concerns the doctrinal aspects of the text. Critical signs, for example, may mark variant readings in the text or indicate passages with dubious authority.

Diagrams, drawings, sketches: this tag indicates that the manuscript contains diagrams, drawing or other visual items added to the text.

Excerption mark: a sign that indicates the beginning or the end of a section that was to be excerpted from the main text, for example, into a florilegium.

Neums: a form of musical notation used in the Middle Ages, consisting of dots, lines and squiggles.

Nota signs: a monogram built up from the letters of the word NOTA (Lat. ‘pay attention!’) that was used in the early Middle Ages to mark passages of interest.

Quotation signs: a type of sign used in the early Middle Ages to mark citations present in the main text. Unlike in modern times, citations were not marked regularly in the Middle Ages, and they were not indicated directly in the text, but rather in the margin.

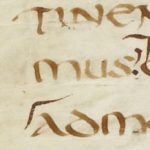

Reading cue: elements added to the text to enhance its readability or navigability. Examples of reading cues include punctuation and word-division signs, accents and hyphens, but also chapter numbers, marginal keywords and running titles.

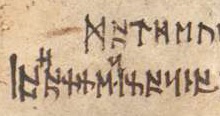

Runes: this tag indicates that the manuscript contains marginalia in runic alphabet.

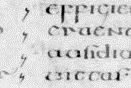

Source references: a conventionalized combination of letters that refers to an author or a text, usually a Church Father or a book of the Bible. Source references were sometimes used in the early Middle Ages to indicate the source of a particular quotation or material incorporated in an excerpt collection. The most common source reference include AG for Augustine, GG for Gregory the Great, and HIR or H for Jerome.

Technical signs: any kind of sign other than the ones subsumed under correction signs, critical signs, quotation symbols and nota signs.

Tie marks: graphic symbols used to connect the main text to a marginal note or a part of a commentary also known as signes de renvoi. Tie marks form pairs of identical symbols, to be used (generally) on the same page. Sometimes they provide a link between pieces of text on different pages.

Tironian notes: a type of shorthand used in the early medieval period. We indicate whether some of the marginalia in the manuscript, for example marginal notes or corrections, were made in Tironian notes.